GRAND FORKS — University of North Dakota President Thomas Kane probably felt a little sheepish in the spring of 1930. He was about to award an honorary degree to a former student who had been the bane of existence for one of his predecessors.

That predecessor, Dr. Webster Merrifield, would have been rolling over in his grave that day as Vilhjalmur Stefansson, a student there in 1902, was awarded an honorary Doctor of Laws degree, only the third in the university’s existence.

It was a surreal day in Grand Forks, as Stefansson was a thorn in Merrifield's side for much of his time on campus. Imagine an early 20th-century northern plains rendition of "Animal House," with Vilhjalmur Stefansson assuming the role of the troublemaker, akin to Otter or Bluto of Delta House, and Merrifield as authority figure, Dean Vernon Wormer.

As unusual as it must have felt, UND leaders had reason to honor Stefansson 28 years after his wild days on campus. He had become a famous Arctic explorer, gaining international acclaim not just for his polar discoveries, but for promoting a meat and fat-based diet long before anyone else.

ADVERTISEMENT

Drawn to the north

Perhaps, it’s not surprising that Stefansson, with his Icelandic ancestry, was drawn to the north. He became famous for spending two decades on Arctic expeditions from 1904 to 1924. For ten winters and 13 summers he lived on the land, inserting himself into the culture of the Inuit Tribes of Alaska, Canada and Greenland.

He became a champion of the Arctic Circle, not as a frozen wasteland but as a region with the potential to be the world’s meat basket and a route for air transport linking Europe, America, and Asia.

During his time up north, he ate the way the Inuit population ate — heavy on animal meat and fat from reindeer, muskox, and fish. During one period of time, when he lived on floating ice in the Arctic Ocean, he survived by eating polar bears and seals.

Stefansson conducted experiments on the benefits and drawbacks of living primarily on animal flesh and preached on the Biblical righteousness of consuming fat. In 1928, he became a guinea pig of sorts, entering Belleview Hospital, where he and a colleague lived on water and a diet of 80 percent beef and mutton fat.

When asked how he was doing, Stefansson replied, “Never felt better!”

Stefansson became a popular international speaker, author, and writer for the next three decades. He shared stories from the Arctic and touted the benefits of a high-protein/low-carb diet long before Dr. Robert Atkins ate his first protein ball.

That international acclaim led to Stefansson's honorary doctorate at his former alma mater. But the story of his days at UND might be the most exciting part of this explorer’s adventure.

At 15, herding cattle and teaching class

Vilhjalmur Stefansson was born Nov. 3, 1879, in a cabin on the shore of Lake Winnipeg in Arnes, Manitoba. His parents were among the first Icelandic immigrants to settle in the region. Hoping to blend into their life in Canada, they chose to name their son William Stephenson. However, in college, perhaps hoping to recommit to his roots, Stefansson dropped the Anglicized spelling of his name for the Icelandic version–Vilhjalmur Stefansson

ADVERTISEMENT

Stefansson was only about 18 months old when flooding in Arnes forced the family to move south to Pembina County, North Dakota.

Stefansson attended country school, and by the time he was 15, he was herding cattle and teaching. He hoped to earn money to attend the University of North Dakota. By 18, he enrolled. A mischievous college career, eventually leading to expulsion, was underway.

Stories and rumors were still circulating 25 years ago about why this now-famous man got the boot, according to a1927 story from The Forum.

“There are many stories afloat about that expulsion. Every alumnus of the university seems to have a different one and each one, as it is told is ‘the truth’,” as written in the newspaper.

Stefansson told The Forum in 1958 that he’s been blamed for every prank on campus over the years, but was he guilty?

“There is some truth in most of them, much truth in some of them, and only a few are entirely false,” he said.

The rumors: football players, staying up late and faculty romances

In 1927, Stefansson addressed the rumors with The Forum.

He said the technical reason given for his expulsion from UND in 1902 was his absence for three weeks without permission. (He had taken a substitute teaching job in Kindred to earn money).

ADVERTISEMENT

Stefansson said when Dr. Merrifield came to his room at Budge Hall to tell him he was expelled he as much as said missing class wasn’t the real reason.

“He was frank, and told me that I was expelled because I was a disturbing influence, that I had undermined the morals of the institution,” Stefansson said, “But I learned later that Merrifield himself never really believed that.”

The football players

One of the most enduring rumors about Stefansson’s expulsion centers around him helping some UND football players cheat in German class.

Stefansson said he found language easy. Some football players in his class did not. They often sought his help with translating homework assignments. But when it came time to answer questions about the homework in class from Professor John Macnie, the players fumbled.

When they once again asked Stefansson for help he told them it was a great bother for him to keep translating for them every night. Instead, he offered to answer the questions in class for them. He said because of Professor Macnie’s poor eyesight, he’d never know the difference if he pretended to be each player.

“Macnie was absent-minded and as near-sighted as he could be,” Stefansson said.

Stefansson and the players got away with it for about three weeks. But then President Merrifield found out and once again visited Stefansson in his dorm room, asking, “Stefansson, don’t you think you are treating Professor Macnie rather shabbily?”

Stefansson replied, “These football heroes can’t be expected to furnish both brain and brawn. They are furnishing the brawn, and I’m furnishing the brains, and in that way, I’m helping carry on the glory of the university. You can’t get along without these football heroes.”

ADVERTISEMENT

Stefansson later claimed that Merrifield laughed and he continued helping the players until the gridiron season ended.

An interesting note: the players he helped did okay for themselves. Two became prominent lawyers in Washington, D.C and the other became Chief of Surgery at a large hospital in Missouri. (They probably didn’t speak German to their clients or patients.)

The lights scandal

In the fall of 1901, Stefansson was assigned a room in Budge Hall, a newly constructed men’s dormitory. His run-in with the professor in charge of the dorm is another rumor that led to his expulsion.

Stefansson explained to The Forum that UND had a lights-out policy at 10 p.m. every night. His roommate Hank Devaney, “a studious fellow,” often broke the rules and was caught studying in the closet with a candle. Perhaps, that’s why the professor in charge of the dorm, John Cox, was so hard on Devaney and Stefansson another night when they were caught up past 10 p.m. with friends.

Devaney jumped into bed, still dressed, and pulled up the covers. Two friends went into the closet and another crawled under the bed. Unfazed, Stefansson decided to stay exactly where he was during the party.

“I sat in a chair, my mouth filled with weinerwurst and a cracker in my hand,” he told The Forum.

When Cox stormed into the room, he was furious and threatened to expel Stefansson for proudly flaunting his rule-breaking.

The professor’s sleigh ride

Stefansson said he believes much of his trouble started when he wrote a poem about a suspected romance between a professor and a female student.

ADVERTISEMENT

Stefansson said that after spotting Prof. Vernon Squires on a horse-drawn sleigh ride with Miss Ethel Wood (whom he would later marry), he decided to have a little fun with it, writing a poem about the sleigh ride.

There is some truth in most of them, much truth in some of them, and only a few are entirely false.

Stefansson said students in the commercial department obtained it, made copies, and distributed them throughout campus.

“The next day all of the students were reciting it, chanting it, and singing it,” Stefansson said.

He said life got challenging for Squires after that and he resigned for a short time to take a job in Michigan. He later returned to UND and became a dean.

Stefansson said the faculty never forgot what he did.

Funeral procession

Whatever straw it was that broke the camel’s back, Stefansson was expelled and given three days to clear his belongings out of Budge Hall.

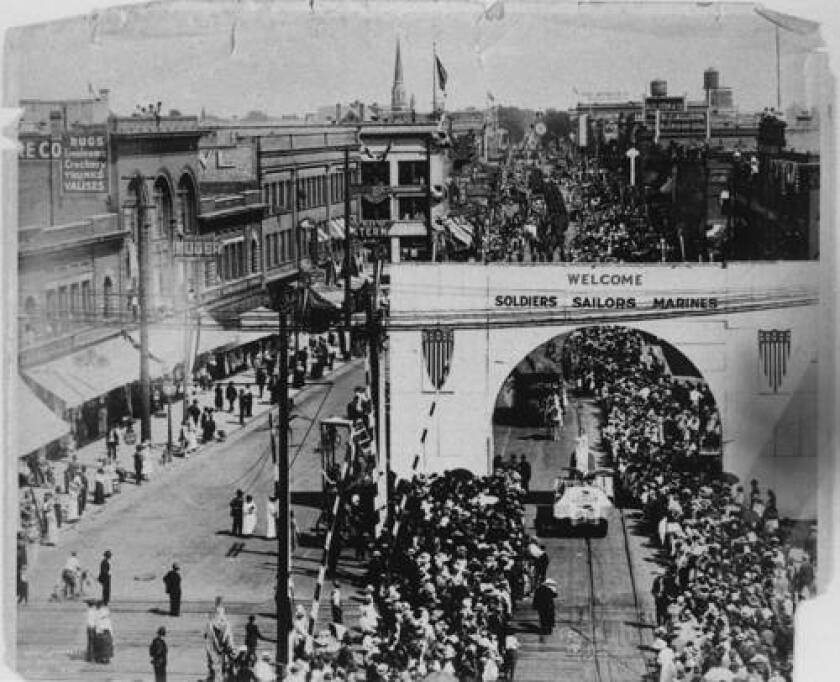

He decided to take every last moment until that very last day and go out in style. He and his buddies decided to hold a funeral. A hearse surrounded by pallbearers drew up to Budge Hall, and Stefansson on his bier was carried out.

ADVERTISEMENT

Stefansson told The Forum in 1927 that they thought of everything.

According to the paper, “May Hinzle, garbed in black and carrying an onion in her handkerchief, was his ‘widow'.

Another friend played the funeral march on his trumpet, and the funeral procession went through campus right past Dean Babcock’s house and downtown to a hotel where a room had been rented and filled with flowers. No doubt a wake was held afterward.

Landing on his feet in Iowa

After getting kicked out of UND in 1902, Stefansson landed a job reporting for a Grand Forks newspaper named the Plaindealer. He earned enough money to try another college.

This time, it was the University of Iowa. Stefansson didn’t mention any hijinx there. Perhaps he buckled down and got serious. After just a year of study, he graduated from Iowa with a Bachelor of Philosophy degree in 1903.

He then went to Harvard Divinity School on a scholarship. His goal was to become a preacher, but he lost interest and turned to a graduate degree in anthropology. His work at Harvard led to an Anglo-American polar expedition, setting his career path.

In addition to his work on the meat diet, Stefansson explored several islands and worked with the native people of Greenland, some of whom had never seen a white man before. After seeing their blonde features, Stefansson deduced they were descendants of Vikings who settled in Greenland.

Stefansson was also part of a famous Arctic sea disaster. He was one of ten scientists aboard the wooden-hulled Karluk, which departed Canada for the western Arctic in June 1913, but it never reached its destination after getting trapped in ice and eventually drifting to Siberia. Eleven men were killed.

Stefansson published 24 books and 400 articles about his adventures and was awarded honorary degrees from UND, the University of Iowa, Harvard University and universities in Michigan and Iceland.

Later, he worked as a professor and Arctic consultant for Dartmouth College in Hanover, New Hampshire.

His days of polar exploration and college troublemaking became part of his past. The most adventurous or scandalous thing the papers had to say about him in later life was from a story in The Forum in 1959 when he agreed to “sample” a piece of cake on his 80th birthday.

Three years later, Stefansson suffered from a stroke and died on Aug. 26, 1962.

Stefansson left behind an impressive resume in polar exploration, education, and nutrition.

His past pranks at UND had been forgiven. He visited the state often, lecturing at the university and accepting his honorary degree. He told reporters he always considered North Dakota his home.

The world might remember Vilhjalmur Stefansson as a pioneer of polar exploration. But North Dakota also remembers the "disturbing influence," who turned out okay.

STEP BACK IN TIME WITH TRACY BRIGGS

Hi, I'm Tracy Briggs. Thanks for reading my column! I love going "Back Then" every week with stories about interesting people, places and things from our past. Check out a few below. If you have an idea for a story, email me at tracy.briggs@forumcomm.com.