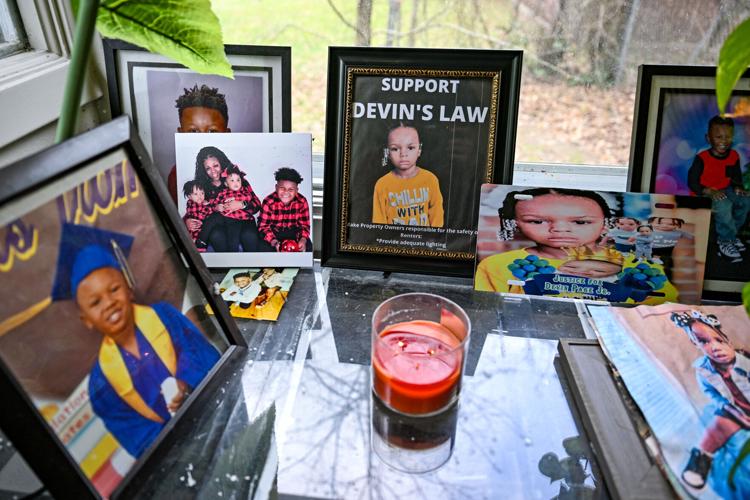

Cathy Toliver had just finished a video call with her grandson Devin Paige Jr., who she referred to as “snickerdoodle.”

It was late on the night of April 12, 2022. Toliver told the boy in Baton Rouge she would see him the next day, kissing the 3-year-old goodnight over the phone.

Then 45 minutes later, Toliver received a reality shattering phone call from her daughter, Tye Toliver, the boy's mother.

“Mama!” her daughter screamed. “They just killed my baby!”

In the following days, when grief-stricken family members visited the crime scene in the city's Fairfields neighborhood, they saw 39 pieces of tape along the walls of the adjacent house, as law enforcement had marked each bullet hole.

A 40th bullet had shattered Devin’s bedroom window.

Almost three years later, investigators have yet to identify the gunman responsible for Devin’s death. What is clear: The assailant didn't target the Tolivers' home, but used a weapon equipped with a machine gun conversion device to fire a barrage of bullets in a matter of seconds, one of which strayed into Devin’s bedroom and killed him.

“That baby was sleeping in his bed, not bothering anybody,” Toliver, his grandmother, said. “It had nothing to do with us.”

Daughter and mother Tye and Cathy Toliver hold hands at Cathy’s home on Wednesday, March 19, 2025.

More commonly called Glock switches for pistols or auto sears for rifles like AR-15s, the conversion devices are quarter-size contraptions that attach to the back of a gun's slide. They transform semi-automatic firearms into fully automatic machine guns, allowing a shooter to fire multiple rounds with a single trigger pull.

Conversion devices are quarter-size contraptions that attach to the back of a gun's slide. They transform semi-automatic firearms into fully automatic machine guns, allowing a shooter to fire multiple rounds with a single trigger pull.

Guns with conversion devices fire about 20 rounds per second on average, or 1,200 rounds per minute, a firing rate that would require special clearance for military personnel.

Despite a 2023 Louisiana law making it easier for law enforcement to crack down on possession of conversion devices, East Baton Rouge Parish District Attorney Hillar Moore said he's seen use of switches and sears continue to proliferate due in part to their cheap, easy access online and insidiously trendy nature.

Since the law went into effect, the number of criminal cases involving fully automatic weapons in East Baton Rouge jumped from six in 2021 to 78 through October 2024.

“Everyone that we deal with has access to an auto sear,” Moore said. “If you're a bad guy and want to hurt someone, you probably have an auto sear.”

In 2020, only two incidents of fully automatic gunfire were recorded in East Baton Rouge, according to data from the district attorney's office. By 2024, that number had risen to 214, an average fourfold jump a year that has mirrored national trends.

“I would say before 2019, I’d never even heard of them,” Baton Rouge police Detective Zach Woodring said. “Now, I couldn’t even tell you how many cases we get.”

Woodring is a member of Baton Rouge's gun police, serving with the department's Crime Gun Intelligence Center and the local Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms, and Explosives task force. About 80% of the group's investigations are gun crimes involving the gun conversion devices, he said.

'I'm cool' factor

Often made using 3D printers, the devices are alarmingly available for anyone with $30 and basic knowledge of navigating the dark web.

“They’ll pretend they are shipping other things, and you can order packets,” Woodring said. “It's basically all coming from China.”

The gun maker Glock Corp., doesn't manufacture, market or sell these conversion switches for its firearms, according to the ATF.

The devices also have become deeply entrenched in Baton Rouge gun culture, Woodring said, particularly among young males who are disproportionately involved in the city's homicides. He thinks the demographic is increasingly drawn to them for the perceived status they afford.

“A lot of it is internet clout,” Woodring said. “Like ‘if I have a Glock switch I’m cool.’”

The silver machine gun conversion device, or "glock switch," attached to the back of a pistol's slide.

Glock semi-automatic pistols have been a staple in mainstream rap lyrics for years, even inspiring artistic monikers like Key Glock, a popular Memphis rapper.

Now, the devices turning Glocks into machine guns also are appearing in lyrics.

"Keep a switch up on me everyday like it's my favorite clothing line,” raps TREC, a Baton Rouge artist in "Spider-Bang." The 2022 music video for the song received over 800,000 views on YouTube.

Adding to the danger is the way conversion devices make guns “extremely hard to control,” Woodring said.

Living in fear of gun violence

Whether or not the Glock switches and auto sears translate to higher homicide rates in East Baton Rouge is unknown. Law enforcement doesn't compile statistics on the number of the devices used in guns involved in shootings, but they do dramatically increase the potential for collateral damage.

“I think if an individual wants to go shoot somebody, they are going to go do it no matter what they are equipped with,” the police detective said. “... The odds you are going to hit what you're aiming at lessen exponentially with an MCD (machine gun conversion device).”

It may help explain some of the seemingly random killings in East Baton Rouge, or victims like Trevor Harrison, a 27-year-old plumber who was shot and killed in a crossfire in February.

In a city where much of the gun violence stems from retaliatory measures among criminal groups, the technology has helped spark paralyzing fear in high-crime neighborhoods, like the Baton Rouge neighborhood where Devin was shot.

“Back in the day, you didn’t have access to that,” Toliver said, of the conversion devices that make guns even more deadly. “Now you're not even safe in your own home. … If you talk to older people, they’ll tell you ‘no, I’m not going outside.'"

Rare bipartisan push on gun policy

In June 2023, Moore, the East Baton Rouge district attorney, and the state’s district attorneys lobby helped push Louisiana lawmakers to pass House Bill 331, which significantly tightened restrictions on the gun conversion devices.

Spearheaded by Rep. Dewith Carrier, R-Oakdale, who lost his wife and was left paraplegic in a 2010 shooting, the legislation aligns Louisiana law with federal standards, redefining a machine gun as any device firing more than one round per trigger pull.

The streamlined Louisiana law has simplified the prosecution process, eliminating the previous requirement for prosecutors to prove that at least eight rounds were fired with a single trigger pull. Now, mere possession of the Lego-looking gadgets can land someone in prison for up to 10 years.

“Now we have more room to prosecute,” Woodring said.

The bill marked unusual bipartisan alignment on gun policy in a state traditionally known for lenient firearm laws. The sole opposing vote in either chamber was cast by Rep. Danny McCormick, R-Oil City.

Across the nation, less than half of the states have laws banning gun conversion devices, though some with normally lax gun laws are starting to follow suit. In Alabama for example, a bill that would ban Glock switches recently passed the House 28-0.

Stiffen the law?

Still, in Louisiana the 2023 law hasn’t yet seemed to stop the flow or use of the gun devices. Meanwhile, federal agencies have similarly struggled, prompting President Joe Biden to sign an executive order last year to help with the crackdown.

“We have a better opportunity to convict you of that offense,” Moore said. “(But) I’m sure there are much more MCDs now than when the law started.”

Judges rarely deliver significant penalties to people in possession of the gun devices, Woodring said, and bonds are usually set below $5,000. He has seen individuals bond out at less than $100, creating a revolving door of repeat offenders in the courts system.

“We keep catching the same people over and over,” the police detective said. “No one is stressing about being caught.”

In addition to stricter sentencing, Moore thinks the law itself could be more effective. Carrying conversion devices is still not a “prohibitive offense,” meaning those convicted of possession can continue to buy firearms.

“The gun lobby made it really clear to us that we are not making it a prohibitive offense.” Moore said. “What we took at the time was a compromise."

'Not going to stand for it'

From left to right, Tye Toliver, son Tyren Young, 12, mother Cathy Toliver and daughter Deiyauna Page, 4, pose for a picture together while holding photos of Tye's late 3-year-old son, Devin, at Cathy’s Baker home on Wednesday, March 19, 2025. Devin was killed three years ago from a stray bullet that struck him in his bedroom.

After the 2022 death of her grandson, Toliver became an outspoken advocate against gun violence in Baton Rouge. She has worked with former Police Chief Murphy Paul, and now Chief Thomas Morse Jr. to organize vigils for gun violence victims. Last year, she visited Washington, D.C., to meet with Vice President Kamala Harris.

The 62-year-old makes a point of walking freely through high-crime areas in Baton Rouge, despite having had multiple guns pointed at her face. For her, it is the most effective way of letting others know despite increasingly powerful weapons, she isn’t intimidated by those pulling the trigger.

“I want to let them know that we’re not going to stand for it,” she said. “I will not walk in harm's way, but I will walk freely wherever I want to go.”