Geoffrey Bawa’s furniture designs are revived – a tropical modernist treat

Bangalore studio Phantom Hands cultivates the furniture legacy of Sri Lankan tropical modernist pioneer Geoffrey Bawa

Sri Lankan architect Geoffrey Bawa remains the archetypal exponent of tropical modernism, an architecture of innovation and adaptation that meshes contemporary materials and techniques into all the variables of a warm and humid climate. Trained first as a lawyer, Bawa studied at the Architectural Association in London before returning to his homeland.

From the late 1950s onwards, Bawa built extensively in Sri Lanka, as well as in India, Indonesia and beyond. His work spliced vernacular forms and layouts with a stripped-back modern style, frequently using local craft techniques in new and unconventional ways. Throughout his career, Bawa designed bespoke furniture for his projects, again working with local artisans and suppliers, with a rough-hewn approach that was a literal world away from the precision-machined finishes of the work flowing from the Bauhaus diaspora.

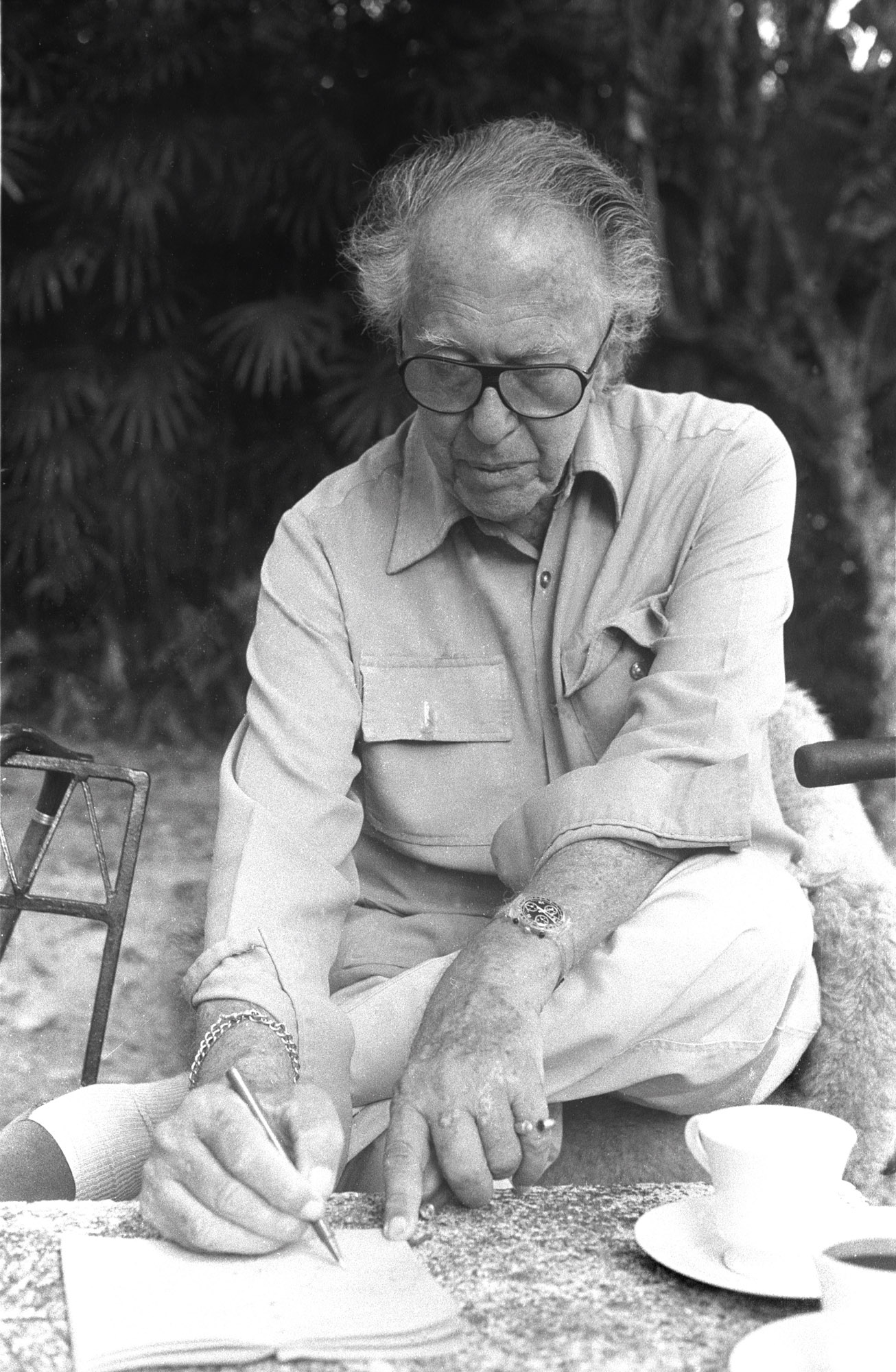

Geoffrey Bawa in his garden in Lunuganga in 1996

Now, for the first time, those furniture designs are being revisited and reissued, not as faithful one-to-one replicas, but as ‘reinventions’, carefully stewarded to production by the Bangalore-based furniture company Phantom Hands. Working alongside Channa Daswatte, Bawa’s close collaborator in his final years and now chairperson of the Geoffrey Bawa Trust, Phantom Hands has spent more than 18 months researching and evolving 20 key pieces from Bawa’s career, 17 of which have just made their debut at Milan Design Week 2025.

The project has strong parallels with Phantom Hands’ first furniture collection, a series of re-editions of Pierre Jeanneret works originally designed for the Indian city of Chandigarh. Phantom Hands’ Bangalore workshops house more than 100 artisans, local craftspeople that are bringing modernist designs back to production reality with modern market demands.

Phantom Hands’ re-edition of the ‘Kandalama’ chair is available in anodised black and aluminium versions, seen here as prototypes in the Phantom Hands workshop

Aparna Rao, who co-founded the studio with Deepak Srinath in 2014, describes the new project as fulfilling Bawa’s legacy, as well as recontextualising the work for a modern audience. ‘The question we always asked was, “Do we think this is a nice table or chair even if we didn’t know Geoffrey Bawa had designed it?”’ she says. As with many great ideas, the collection, titled ‘Geoffrey Bawa re-edited by Phantom Hands’, came about partly by chance. Rao was working as an installation artist in Zurich, partnering with ETH’s robotics lab, when she was introduced to Daswatte who was looking to license the production of Bawa’s furniture.

Across four decades of practice, the architect shaped more than 100 distinctive pieces. Some were fashioned crudely from off-cuts of building materials, giving them the feel of an objet trouvé. Other pieces were more experimental, making the most of scarce materials at a time of great civil unrest in the country.

‘Lunuganga’ table from Phantom Hands’ ‘Geoffrey Bawa Collection’

Rao and Srinath began by committing to making reproductions of six key pieces, slavishly following any idiosyncrasies of design and construction. The ‘Lunuganga’ table, originally designed for Bawa’s 12-acre country estate in Bentota, had ‘crude welding’, according to Rao. ‘This was the charm of tropical modernism,’ she says. ‘Working on an island without big industry, Bawa didn’t think it was important to be precise. We were honest in replicating the dimensions exactly, even if they weren’t completely consistent.’ This was also the case with the ‘Kandalama’ chair, first seen at the hotel of the same name, a dramatic structure rising above the jungle canopy that has become one of the architect’s best-known works. ‘We replicated the irregularities as closely as possible to the original,’ Rao says of the bent and welded metal slats.

Wallpaper* Newsletter

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

‘Kandalama’ café chair from Phantom Hands’ ‘Geoffrey Bawa Collection’

However, something was missing. ‘There was a long period of feeling a bit paralysed [by the project],’ she says. ‘The pieces didn’t seem to sit well together.’ Partly this was because Bawa often designed a piece for a very specific location. ‘He sometimes made a piece of furniture in an afternoon – it was a prototype, rather than a finished piece,’ Rao explains. ‘What we see with his furniture is a starting point. Therefore the pieces seemed a bit lost outside their context.’

As a result, the strict replica approach was reassessed. Bawa was tall, and proportions and sizes had to be changed to make chairs more inclusive. Fabrics were made more durable and resilient. Other elements and details were also changed to facilitate production, but it wasn’t until Rao and Srinath visited the Kandalama hotel that they had a breakthrough. Rao says the project revealed a different side of his vision.

‘Kandalama’ bench from Phantom Hands’ ‘Geoffrey Bawa Collection’

‘Bawa was always asking a question with his furniture, about function and intention,’ she says. ‘Seeing the furniture in the context of the hotel, where human habitation is adjacent to plants and animals, was important.’ She cites the ‘Kandalama’ bench, a flexible piece that seemed to mimic the way the local monkeys sat together as a family group, while also having a simplicity that allowed for the appreciation of the space, both architectural and geographical.

Daswatte confirms this. ‘Bawa worked to design furniture, objects and art to enhance the experience within the spaces he created,’ he says. ‘So yes, very often the furniture for each project was unique, be it a newly designed piece or something selected from the rich history of traditional and colonial Sri Lankan furniture.’

In re-editing these designs for a wider audience, Phantom Hands has been able to develop and evolve each piece. ‘Part of Bawa’s process was that he mentored people and let them develop by allowing them to iterate and work things out,’ Rao says. Strong ideas were fused with strong craftsmanship, which, in turn, helped transform waste material into a beautiful object, like a stone lamp base.

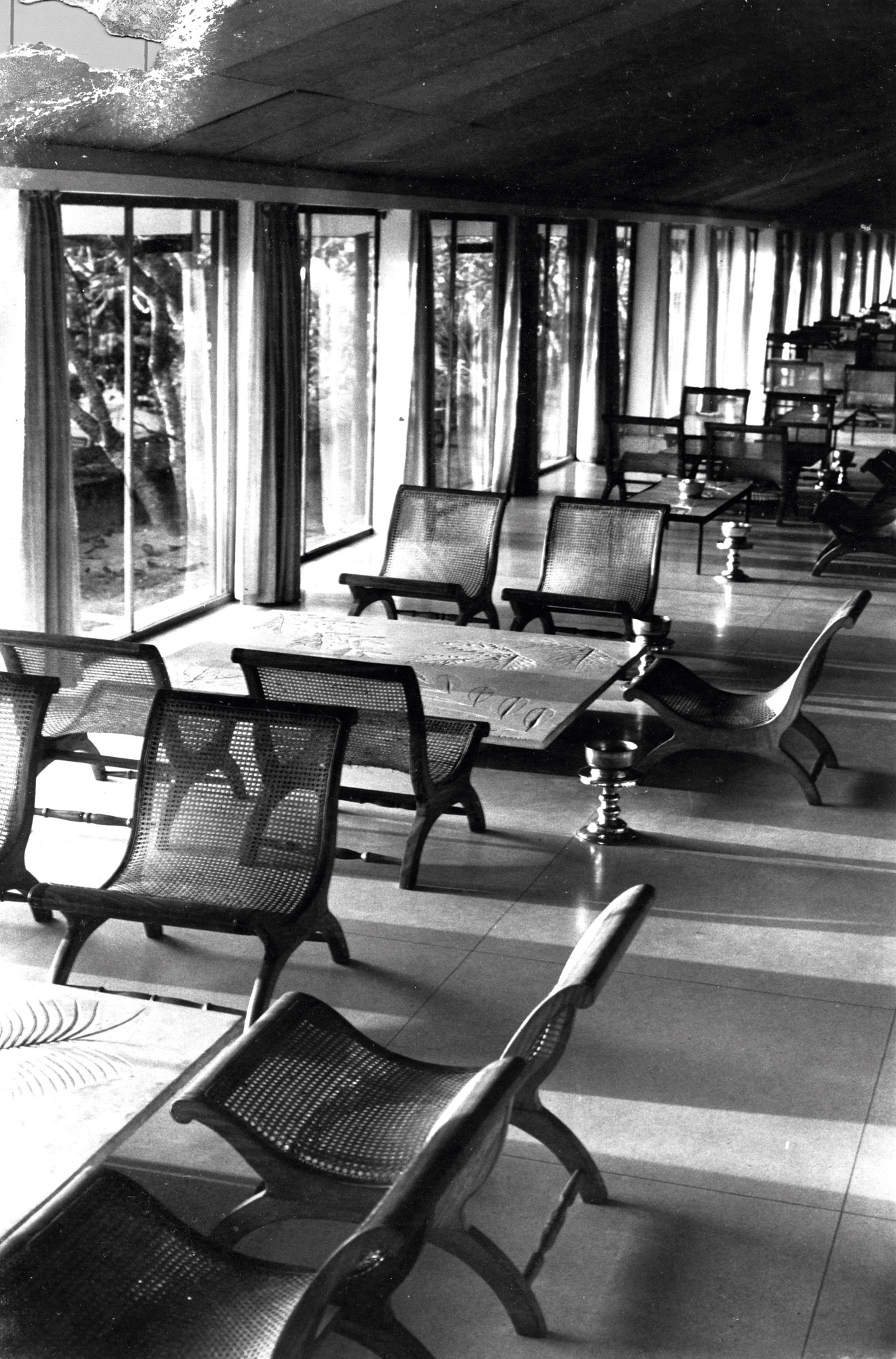

The Bentota Beach hotel in Sri Lanka was designed in 1967 by Bawa, who also created its furnishings, such as these wood and cane lounge chairs

Over the course of the project, Phantom Hands researched almost all of Bawa’s designs, from one-offs to items such as the ‘Saddle’ chair, seen in the bar of the Neptune hotel in Beruwala, Sri Lanka, as well as in the Madurai Mills club in Madurai, India. Pleasing idiosyncrasies abounded.

‘Bawa was a serious smoker,’ Rao says of the ‘Kandalama’ ashtray, a triangular container atop slender metal legs. ‘He designed this object for someone to reach behind them to flick their cigarette ash on to when they’re seated at a dinner table.’ Then there are the bespoke door handles in Bawa’s own house, inspired by the branches of a specific (and still surviving) tree in the garden.

‘Kandalama’ ashtray from Phantom Hands’ ‘Geoffrey Bawa Collection’

‘It all comes back to the idea of a zero-waste economy,’ concludes Rao, citing other examples of found and recommissioned objects, like the stone bench in Bawa’s house that served as a dog bed, or his writing table consisting of two filing cabinets topped with a roughly cut slab of marble. ‘Bawa had a real sense of order,’ she says. ‘He achieved harmony despite the varied nature of the objects, textiles and art within a space. A piece of furniture was never meant to be the antagonist – it was always meant to be read as part of a collection of objects.’

Metal and stone lamp from Phantom Hands’ ‘Geoffrey Bawa Collection’

As if to reinforce this idea of an ever-evolving realm of things, Rao tried her hand at adapting one of Bawa’s unfinished designs. ‘Channa supplied us with some sketches of unbuilt designs, including a portable ashtray with a coconut shell cover,’ she says. ‘I thought it was such a beautiful idea and turned it into a prototype, although I used a ladle instead of a coconut.’ Sri Lankan architect Palinda Kannangara helped refine the design. ‘In that way, I experienced the way designs can pass through many minds and get better,’ says Rao. ‘It helped drive this shift from “reproduction” to “re-edition”.’

‘Saddle’ chair in burgundy from Phantom Hands’ ‘Geoffrey Bawa Collection’

The final 20 pieces, all made by Phantom Hands, demonstrate various aspects of this philosophy, from making elements demountable to help with shipping to increasing the durability of textiles and leathers. ‘The finished collection embodies Bawa’s work away from his buildings,’ Rao says. ‘They improve the sense of authenticity. Channa gave us the confidence to be free from simply replicating things – he was convinced that this is what Bawa would have done if he could.’

For Daswatte, Phantom Hands were safe hands. ‘They not only make an effort to trace the provenances of all the furniture they produce, but consider contemporary concerns such as sustainability,’ he says. ‘These were issues that Bawa himself was concerned with. Moreover, a visit to their workshops in Bangalore reaffirmed our interest in working with a company that has very good working relationships with the artisans, designers and owners.’ As a result, this master of form and material gets a much-deserved wider audience.

‘Design in the Moment’, an exhibition of the ‘Geoffrey Bawa re-edited by Phantom Hands’ collection, was shown at the Inoda + Sveje Gallery, Milan, during Milan Design Week 2025, and is on view at The Bawa Space, Colombo, Sri Lanka, until 31 May 2025, geoffreybawa.com, phantomhands.in, gallery.inodasveje.com

This article appears in the May 2025 issue of Wallpaper*, available in print on newsstands from 3 April 2025, on the Wallpaper* app on Apple iOS, and to subscribers of Apple News +. Subscribe to Wallpaper* today

Jonathan Bell has written for Wallpaper* magazine since 1999, covering everything from architecture and transport design to books, tech and graphic design. He is now the magazine’s Transport and Technology Editor. Jonathan has written and edited 15 books, including Concept Car Design, 21st Century House, and The New Modern House. He is also the host of Wallpaper’s first podcast.

-

Ligne Roset teams up with Origine to create an ultra-limited-edition bike

Ligne Roset teams up with Origine to create an ultra-limited-edition bikeThe Ligne Roset x Origine bike marks the first venture from this collaboration between two major French manufacturers, each a leader in its field

By Jonathan Bell

-

The Subaru Forester is the definition of unpretentious automotive design

The Subaru Forester is the definition of unpretentious automotive designIt’s not exactly king of the crossovers, but the Subaru Forester e-Boxer is reliable, practical and great for keeping a low profile

By Jonathan Bell

-

Sotheby’s is auctioning a rare Frank Lloyd Wright lamp – and it could fetch $5 million

Sotheby’s is auctioning a rare Frank Lloyd Wright lamp – and it could fetch $5 millionThe architect's ‘Double-Pedestal’ lamp, which was designed for the Dana House in 1903, is hitting the auction block 13 May at Sotheby's.

By Anna Solomon

-

Lasvit brought forest, fabric and frozen light to Euroluce 2025

Lasvit brought forest, fabric and frozen light to Euroluce 2025Czech glassmaker Lasvit’s 2025 lighting launches look to nature for inspiration and reflection

By Ali Morris

-

Conie Vallese and Super Yaya’s beribboned bronze furniture is dressed to impress

Conie Vallese and Super Yaya’s beribboned bronze furniture is dressed to impressTucked away on the top floor of Villa Bagatti during Milan Design Week 2025, artist Conie Vallese and fashion designer Rym Beydoun of Super Yaya unveiled bronze furniture pieces, softened with hand-dyed ribbons in pastel hues

By Ali Morris

-

Tectonic modernity makes for fine dining furniture from Knoll

Tectonic modernity makes for fine dining furniture from KnollThe new ‘Muecke Wood Collection’ by architect Jonathan Muecke for Knoll brings artistry to the table

By Hugo Macdonald

-

Elegance personified, the 'Riley' sofa is a handsome beast

Elegance personified, the 'Riley' sofa is a handsome beastA new sofa by Hannes Peer for Minotti has us swooning, not slouching

By Hugo Macdonald

-

At Milan Design Week 2025, Turri launches a circular dining table fit for ceremonial feasts

At Milan Design Week 2025, Turri launches a circular dining table fit for ceremonial feastsThe new ‘Kenobi’ by Marco Acerbis for Turri is the kind of dining table we like to get around

By Hugo Macdonald

-

All hail Jil Sander’s first foray into furniture

All hail Jil Sander’s first foray into furnitureAt Milan Design Week, the venerated fashion designer unveils a respectful take on a tubular furniture classic for Thonet

By Nick Vinson

-

Paola Lenti unveils future-facing ‘Alma’ outdoor seating

Paola Lenti unveils future-facing ‘Alma’ outdoor seatingAt Milan Design Week 2025, Argentine designer Francisco Gomez Paz and Italian brand Paola Lenti unveil ‘Alma’ – a lightweight, technically advanced outdoor seating system

By Ali Morris

-

Milan Design Week: these porcelain lights mimic paper lanterns

Milan Design Week: these porcelain lights mimic paper lanternsAn exclusive first look at Lee Broom's ‘Cascade’ lighting for Lladró, launching at Euroluce during Salone del Mobile 2025

By Hugo Macdonald