Sign up for the latest Boston Marathon updates

👟 Everything you need to know about Marathon Monday, delivered to your inbox.

As the field of 112 runners toed to the starting line of the 1926 Boston Marathon, one of them stood out for a habit that, even in a very different era of distance-running, was unmistakably crazy.

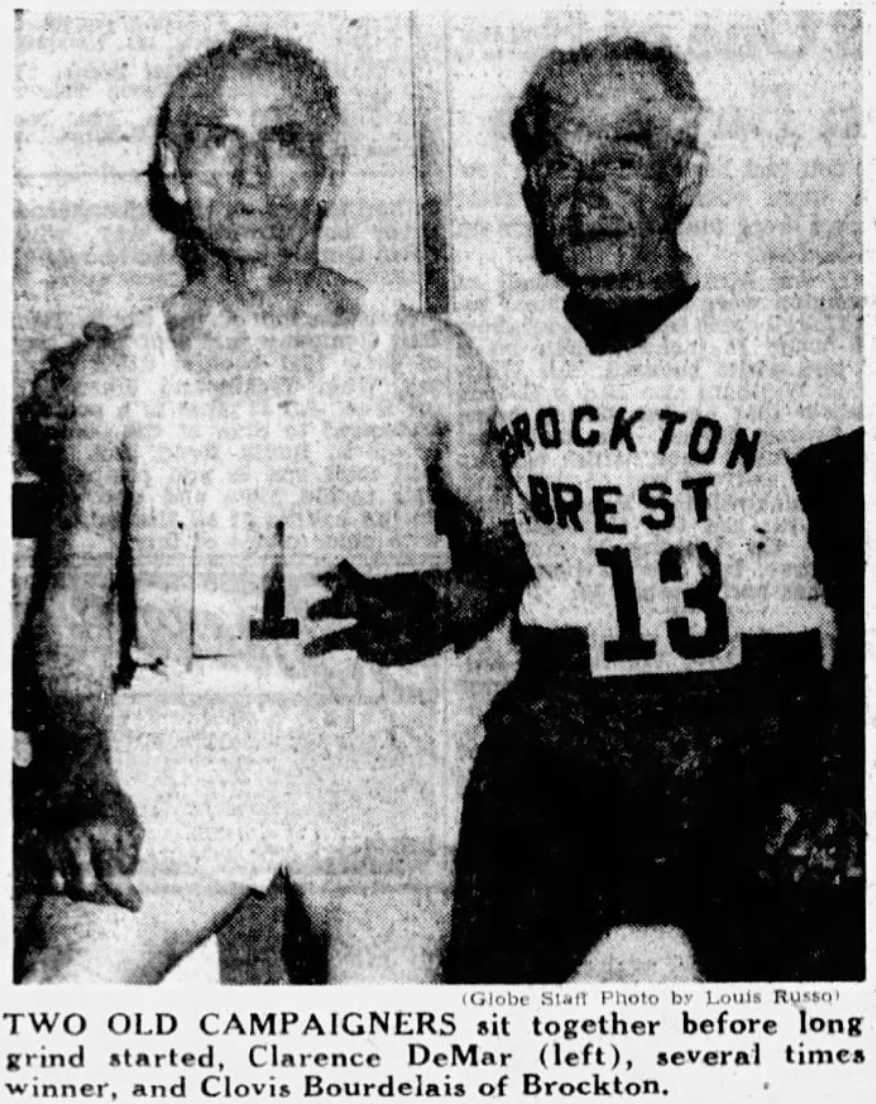

It was not Clarence DeMar, Boston’s (then) four-time champion, nor was it Albin Stenroos of Finland, gold medalist at the 1924 Paris Olympics. Boston Globe writer John J. Hallahan discussed the favorites (including DeMar and Stenroos) at length, but was struck by another image.

“The most surprising thing of the early preparation was the unusual sight of Clovis Bourdelais of the Oko Club of Brockton smoking a cigar,” wrote a bewildered Hallahan. “He started with the weed in his mouth, puffing away and had smoked it out before he reached Ashland about three miles away.

“He said after the race that he smoked two cigars and wanted another,” Hallahan added, “yet this unusual athlete who had garnered honors for bravery in the World War finished 27th in the race.”

Bourdelais’s finishing position within the field was comparatively unremarkable (insomuch as finishing a marathon can ever be regarded as unremarkable), yet his inimitable cigar habit made him an inescapable figure in Hallahan’s recap. It was a microcosm of the Canadian native’s near-half century connection to Boston’s iconic race. He would never be crowned with a winner’s wreath at the finish line, yet in his own idiosyncratic way, Bourdelais left an indelible mark on the event.

In a sense, Bourdelais is one of the earliest examples of a timelessly recognizable component of Boston’s annual marathon. He celebrated the oddities, the resilience, and the inherently grueling demands of the event, and did so with style.

In short, Clovis Bourdelais was one of the Boston Marathon’s original characters, a mantle that generations of bandits and diehard distance runners have embraced since. He ran in the Boston Marathon in five separate decades, setting an early benchmark in what was possible as a long-term marathoner.

His story never led the event’s coverage, and his name appears only intermittently in the official Boston Athletic Association records. But as was the nature of Bourdelais — like all marathon characters to come after — his legacy can be found between the lines of regular headlines and statistics.

Born in Canada in 1890, Bourdelais moved to Marlboro, Massachusetts with his family in the early 20th century. His name first began drawing interest as a runner in 1911, when he set a record in the Saco-Portland road race.

He’d been mentioned earlier in the year as training for the Boston Marathon, but the time was “not recorded,” according to a 1925 Globe account. In 1912, he improved, managing 20th place.

Whatever he may or may not have become as a runner developing into his prime, Bourdelais’s life — like millions of his generation — was irrevocably changed by the onset of World War I.

As a native Canadian, he enlisted earlier than most of his U.S. peers, and by 1915 was writing home from England. A Globe account from July, 1915 noted that he had won a “‘quality’ honor as a gunner,” though he had yet to be deployed to the western front.

Attached to the Canadian field artillery’s 6th Brigade, Bourdelais was eventually sent to Belgium. Per his post-war account, Bourdelais fought in the first and second battles of Ypres, and was eventually captured by the Germans. Though initially listed in The Toronto Star as “missing” in June, 1916, the Red Cross later confirmed that he was alive and being held in the Giessen prisoner of war camp.

It wasn’t until the war’s end in 1918 that Bourdelais was able to be freed. He reportedly received a personal citation from King George V for his service, though the experience clearly had a traumatic impact on him.

“We were very often worked day and night on little food, and if we refused to follow orders we were given severe punishment,” he told the Globe in 1919 following his return home. “I’m very lucky to be back.”

By 1920, Bourdelais was ready for another shot at the marathon. Interestingly, the B.A.A does not list him as an official finisher in 1920, but the record-keeping for some of the later times in that era was imperfect.

Bourdelais was noted in both the pre-race listing of the field (composed of just 74 runners), and also the Globe’s official results (where he was reported to have finished 20th).

By 1925, he was already on his way to becoming a yearly fixture.

“Almost any afternoon, this well-built young man may be seen darting through traffic on Main St. or speeding along the country roads outside the city,” a Globe story said of Bourdelais’s training regiment. He was by now listed as a Brockton resident. The highest he was cited as having placed in the marathon was 18th in 1921.

What really made him conspicuous, however, was not his place in the standings. Nothing epitomized this more than his 1926 performance in Boston having smoked the cigars to begin the now-26.2 mile event.

It became an annual habit to see Bourdelais’s name listed first among the early Boston applicants. Because it was an era when runners’ bib numbers were occasionally still listed in the order of application instead of the prior year’s standings, Bourdelais wore No. 1 multiple times.

“Instead of some outstanding star of marathons, a virtual unknown will wear the coveted numeral ‘1,’” explained the Star Weekly in 1933.

But the Brockton-based Bourdelais was already something of a known quantity to regular marathon observers. Globe columnist Jerry Nason gave him an extended mention in his 1934 piece about the event’s characters.

“Unknowingly, perhaps, the Brocktonian has included the prize remark of the year in his historical letter,” wrote Nason. “‘I am feeling fine,’ writes Clovis, ‘and hope you are too. I am cutting trees to keep my limbs in shape.”

Nason was careful to pay respect to Bourdelais for his service, noting that he was a “veteran of the highest sort.”

“You’ve probably seen Clovis along the B.A.A. course one time or another during the past 14 Aprils,” Nason explained, adding a reference to Bourdelais’s middling form.

“Several times you’ve seen him cross that white line on Exeter Street [where the marathon used to finish] in twilight or earlier,” wrote Nason. “Whether your sympathies are are with these men who delight in torturing their arches in the long grind or not, you’ve got to admire a guy who will come back for more.”

By the end of the 1930s, Bourdelais was being regularly described as “one of the first entries received for years” ahead of the Boston Marathon or as a “conspicuous name.”

He was firmly entrenched as an annual character of the event, and began deploying an even more idiosyncratic (but fitting) tradition. As the title for bib No. 1 became more competitive, Bourdelais switched to wearing No. 13 each year. Though seen as an unlucky number, he scoffed at the superstition and deliberately chose it whenever possible.

“It’s all the same to me,” he would later say in a 1952 interview. “Nobody wanted [No. 13], so I took it.” A later Associated Press account described Bourdelais wearing 13 as “the number by which he is known to thousands of marathon fans.”

Though he was never a true rival of DeMar (who went on to win seven Boston Marathons), he was a friend and peer of the legendary runner. The two were noted to seek each other out before the race each year, and DeMar even joked in 1944 that Bourdelais “got peeved because I didn’t have time to come over to his house in Brockton and and sample some of his wife’s apple pie.”

Both DeMar and Bourdelais were among the longest-tenured marathoners in Boston at that point, and were tied together as senior figures by the 1950s.

Bourdelais, of course, was still one of a kind. The cigar smoking remained a habit even into his 60s.

“Clovis smoked a stogey as the doctors examined him,” chronicled Tom Fitzgerald for the Globe in 1952. “He was fit as a fiddle, and while he didn’t worry the leaders, Bourdelais didn’t look much worse for the wear and tear when he shambled over the finish line at about 4:30.”

Referenced as the B.A.A “War Horse,” the 35-time marathon participant was finally denied in 1954 prior to the start. He was “disqualified after failing to pass the medical examination” as a 62-year-old.

Bourdelais, a longtime City of Brockton employee who married and had four children, continued to be around the Boston Marathon in later years. His final marathon mention came in 1959, when he was listed as being at the Hopkinton gym, chatting with runners pre-race.

Bourdelais died later that year at the age of 69 (no cause of death was provided). His AP obituary, which ran in newspapers in both the U.S. and Canada, listed him as having run in 35 Boston Marathons through the years, a record for its time. It closed with a line that — inconsistent record-keeping aside — nonetheless feels like a fitting description for Bourdelais and all of the rank-and-file marathoners who have come to Boston in the ensuing decades.

“He never won the marathon, but he always finished.”

Hayden Bird is a sports staff writer for Boston.com, where he has worked since 2016. He covers all things sports in New England.

👟 Everything you need to know about Marathon Monday, delivered to your inbox.

Stay up to date with everything Boston. Receive the latest news and breaking updates, straight from our newsroom to your inbox.

Conversation

This discussion has ended. Please join elsewhere on Boston.com